Cymanfa’r Adar, The Conference of the Birds takes its name from the Persian poem by Sufi poet Attar of Nishapur in which the hoopoe leads the birds on a pilgrimage in search of enlightenment.

A creatively-fuelled, process-driven forum, The Conference of the Birds aspires to perform as catalyst for ‘groupthink’. That is; respectful, non-confrontational dialogue, such as might assist in enabling an urgently needed recalibration of our relationship with the ‘beyond human’ world. In listening to perspectives beyond our own and acknowledging nuance and complexity, we give ourselves a better chance of effecting the collective action needed to arrest our rapidly-accelerating progress along the road to oblivion. It’s about building bridges and sharing stories of hope – but also being truthful. We cannot, must not sugarcoat the dark reality of what we have done, where we stand and what, as a consequence of our actions, we now face.

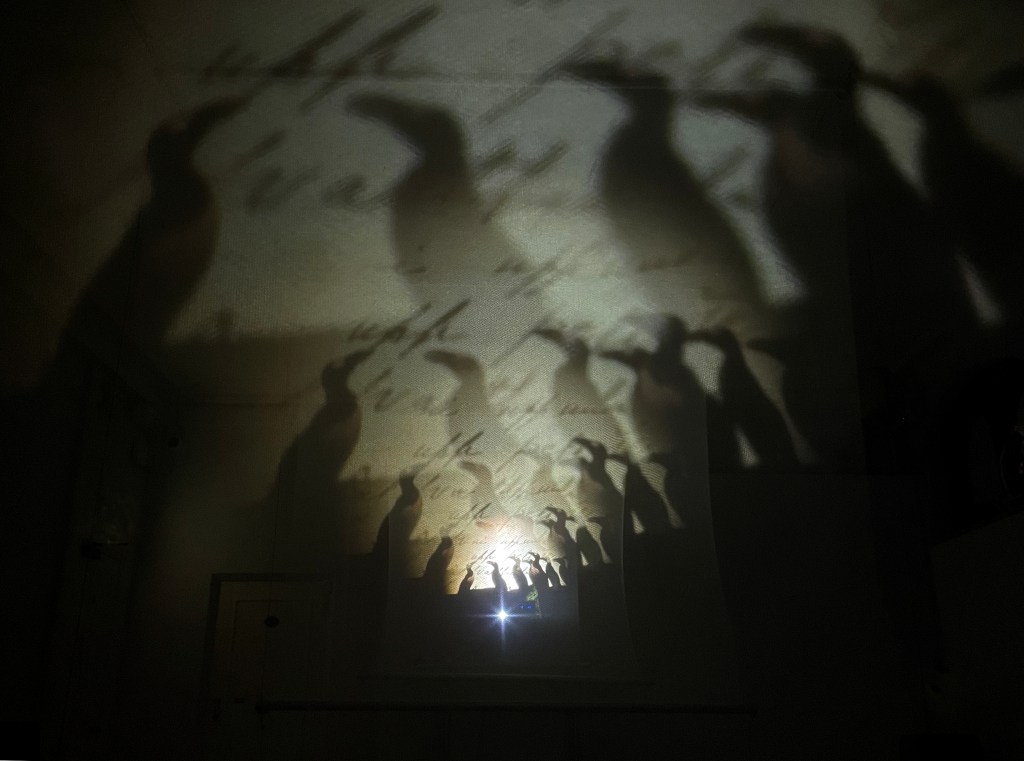

Accordingly, the project is founded on the collaborative realisation and sharing of a diptych of immersive and deeply meditative projection pieces. These ‘beacons’, formed from animated light and sound, are presented alongside smaller animation machines, specimens, objects and works on paper. Functional both indoors and out, collectively they convey stories of time and truth, loss, return and belonging.

In this way, the Conference gives principal voice to two numinous and culturally resonant birds. The great auk was the first bird species to go extinct in the Western hemisphere in historic times; a tragic demise bookended by Welsh science. The Eurasian curlew, the upland farmer’s herald of spring, may be lost from Wales as a breeding species in less than a decade. Together they raise stark questions of our capacity to learn from past mistakes and speak of an unfurling catastrophe with grave consequences for us all. We are nature. If it withers, so do we.

Both then speak of the far-reaching consequences of our actions as producers and consumers and an unsustainable, extractive relationship with the natural world. From distinct biomes with which they are synonymous they advocate for the circularity and inter-connectedness of Earth’s systems. Land management practices in the remote uplands of rural Wales – where the viscerally felt call of the curlew is an increasing absence, a consequence of the imbalance modern society has created – impact directly on the health of the Atlantic ecosystem, the temperature and wider wellbeing of which in turn increasingly affects the viability of food production in both marine and terrestrial habitats.

The great auk stands for the ocean, confronting us with the reality of an extinction event entirely of our making. This avian avatar of the North Atlantic tells us that resources are finite and that if we take too much they will inevitably run out. 1844, a sculptural ‘lantern’ piece, brings to life depictions of the species from the oeuvres of John James Audubon and Thomas Pennant, the eighteenth century Welsh zoologist who gave the bird formerly known as ‘the penguin’ its modern English language name. Our culpability in this loss is confirmed by the sequencing of its DNA – including a sample taken from the heart of the last male bird – by Dr. Jessica Thomas of Swansea University.

This ‘re-animation’ is informed by the memories of great auk movement and behaviour collected from the Icelandic farmer/fishermen who, in pursuit of the specimen collector’s coin, throttled the last reliably sighted pair on the island of Eldey in June 1844. Relayed in words and mimetic movements, the twelve men’s reminiscences of the final expedition were given via interpreter to the Cambridge-based zoologist Alfred Newton and John Wolley in 1858, well over a decade after the event. Newton and Wolley’s handwritten notes from the interviews are contained in the ‘Garefowl Books’ now held in the Cambridge University Library Archive. In the soundtrack for the piece they are given voice by Icelandic anthropologist Gísli Pálsson, author of The Last Of It’s Kind: The Great Auk And The Discovery Of Extinction.

Stop-frame animation, a mimetic act using paper cut-out artwork based on Audubon’s pair of great auks and Pennant’s swimming bird, along with this clear account of the last gasps of the species, provides a deeply focused means to reflect both on this loss and others like it. Accessible to people of all ages, the animation process enables a collective act of memory that is itself founded on memory.

Passing through many hands and minds, a colony of great auks will be assembled to become the central chapter in the work which, through this shared process, becomes a Pan-Atlantic meditation whereby the ocean acts as bridge rather than divide. Echoing a ‘seabird hotspot’ at its centre recently identified by scientists, other species – such as the extant but rapidly declining puffin which carries such cultural resonance in Iceland – may join the Conference as it evolves.

As this initially Wales-based undertaking transforms into an international one, the Numenii – the Curlews; Eurasian, Eskimo and whimbrel, all either red-listed or already extinct – will speak both for the liminal intertidal zones and as migrants who disseminate nutrients across ecosystems. From estuary mudflat to central upland and along the entirety of the West and East Atlantic Flyways, the message they carry is of an existential threat to us all – and that the ocean does not begin or end at our coastlines, rather in our upland streams and urban drains.

By bringing these birds of memory to life in communities across the length and breadth of the North Atlantic we may contemplate what they have to tell us. Within a hypnotic, immersive space we escape the confines of an increasingly polarised and angry society and become more attuned to what unites rather than divides us – and are thus better equipped to find answers to the questions that the great auk and curlew ask of us with such urgency.

Are we willing to do what must be done through the rediscovery of the values held by our forebears: of awe, reciprocity and the sanctity of ‘nature’? We were all indigenous once. The latent capacity to be so again lies within us all.

Y Gymanfa’r Adar, The Conference of the Birds was installed in Senedd Cymru, the Welsh Parliament, Cardiff Bay for three months in autumn/winter 2023 and in Neuadd Goffa Llangynog Memorial Hall in March 2024.