What does ‘nature’ represent to us? A resource or commodity to be managed, exploited, possessed – and something from which we are separate? Or an intangible, omnipresent and all powerful ‘field’, to which we are (at the very least) inextricably connected – if not fully a part of.

These contrasting perspectives represent poles on a spectrum upon which we locate ourselves, our positions dictated by individual experience and culture. If – as seems apt for a ‘Conference of the Birds’ – we take a bird species as being representative of ‘nature’, two specimens presented by Amgueddfa Cymru Natural Sciences curator Jennifer Gallichan at a recent event in the Senedd associated with the exhibition there allow us to contemplate these dual extremes. This in turn, raises some important questions of our society.

The pair of birds in question were a male and female huia: a species unique to New Zealand. The huia is imbued with enormous cultural resonance and power by the Māori to whom it was especially sacred. It’s also quite extraordinary in scientific terms in that the male and female have completely different shaped beaks; the hen’s long and slender, the cock’s stout and stubby. Unsurprisingly, for some time it was mistakenly classified as two distinct species.

In Māori culture the huia symbolises mana – a supernatural force, spiritual power, authority conferred by the tribe – and is tapu: an untouchable, sacred being, connected to that which we might think of as being a ‘god’. Accordingly, huia feathers are invested with the same qualities and were given as tokens of friendship and respect. Only chiefs of high rank wore the distinguished tail feathers in their hair, like jewels within a royal crown.

At an almost (geographically speaking) polar opposite, in Canada archaeologists excavating an ancient ‘Maritime Archaic’ Native Indian cemetery at Port au Choix, Newfoundland unearthed a skeleton covered with the skulls of two hundred great auks and adorned with a bone hairpin shaped into the effigy of a great auk’s head. This, along with the great auk’s enduring presence in indigenous mythologies there, strongly suggests that whilst it undoubtedly offered physical sustenance it was more than just the ‘natural resource’ it was to become to European sailors and colonists. Like the huia it was – and is – charged with resonance, part of the collective memory and value system: of the culture of these peoples.

Sadly the huia, like the great auk, is now extinct; both losses directly attributable to European colonisation. The two species also share the unfortunate distinction of having become increasingly sought-after by collectors as their numbers rapidly diminished. The huia’s spiritual power, cultural resonance and tapu status meant nothing to gentlemen of means eager to display their affinity with the new science through the procurement of marquee specimens for their collections. Demand for feathers of both huia and great auk – the former as fashion accessory, the latter for softening pillows – also contributed significantly to their demise.

Rarity invariably equates to increased value. We crave what we cannot have. In a society of ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ (such as ours is), the capacity to possess that lying beyond the means of the majority confers and expresses status and power. For us today, whatever corresponding concept we had of mana or tapu has by and large been supplanted by the mechanisms of consumerism, by marketability and material exclusivity; all manifestations of the hegemony of the ‘bottom line’. In this universe the Kardashians are revered figures, their way of being an aspiration for so many. The Amazon is not a great river, rather a leviathan corporation which constantly exhorts us to treat ourselves; to boost our sense of well-being via the acquisition of yet more stuff. Within this moral framework, nature – as with everything – is a commodity to be carefully managed; a supply to be controlled. It is owned.

Here in Wales the stories of the huia and the great auk are entwined with a figure who takes this narrative of accumulation and possession to a conclusion of surreal proportions. Whilst never courting celebrity, Captain Vivian Hewitt of Bryn Aber, Anglesey, was a man of unquestionably vast means. In today’s terms his inheritance amounted to a fortune of over £100 million. Amgueddfa Cymru’s huia pair were part of a collection amassed by Hewitt, the scale of which reflects both his wealth and preoccupation with somehow ‘owning’ birds. At the time of his death in 1965 it incorporated well over 500,000 eggs, 100,0000 skins and more than a hundred specimens whose taxidermy was undertaken to commission by Rowland Ward Limited of Piccadilly.

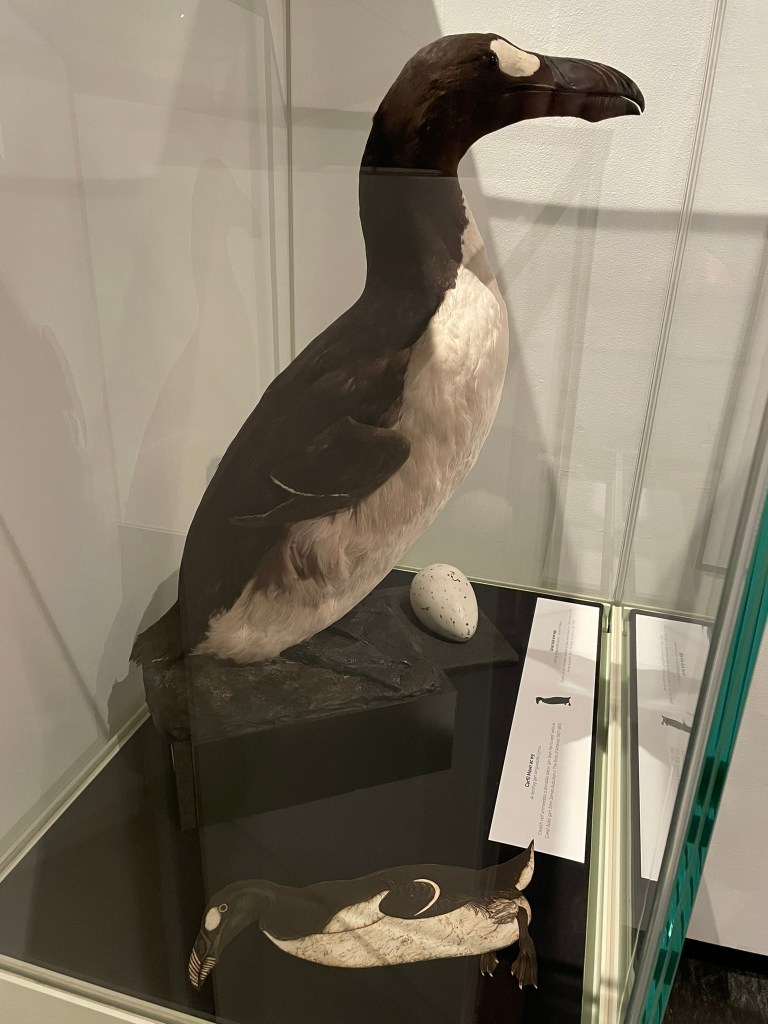

Hewitt was particularly obsessed with the great auk, possessing four taxidermy specimens and a staggering thirteen eggs. The species had been the focus of a wild collector-mania in the late Victorian era, an allure which endures today, thereby presenting a yardstick in contemporary financial terms. When a great auk egg, one of only 75 in existence, was auctioned at Sotheby’s New York in 2021 – the last recorded sale having taken place in 1910 – the pre-sale estimate was $150,000 to $180,000. Taxidermy specimens, of which there are only 78 in the world, are of unfathomable value.

The great auk viewed by thousands of visitors to the Senedd in autumn 2023 as part of The Conference of the Birds is, like the huia pair, in the collection of Amgueddfa Cymru. It was originally purchased in 1948 by Hewitt from Lt. Col. George Malcolm, 18th Laird of Poltalloch – whose family wealth was significantly increased by slave trading. In the course of the ‘hunt’ Hewitt dispatched Peter Adolphe (who was soon to invent the game of Subbuteo) to Scotland to acquire the bird, armed not with a gun but a blank cheque. The mission duly accomplished, the specimen – along with a great auk egg – was driven back to Anglesey and presented to a delighted Hewitt who, having examined his new trophy, carefully placed it back in its container. Here it stayed until its arrival at the auctioneers Spinks and Son Ltd following his death.

Hewitt’s biographer William Hywel observed that:

So easy would it have been to build a special room with display cabinets, where he could have tabulated his specimens and exhibited them with pride. But no, they were hidden away in every conceivable and unlikely corner. His bed-sitting room, as well as the passages were stacked high with countless boxes, and all available drawers were equally crammed. He himself had an uncanny knack of laying his hand on a required box, but he never appeared to have the inclination of showing off his wares to anyone else

Thus, returning to our spectrum, Hewitt the hoarder sits at one pole; that of unbridled, obsessive consumption, of nature as commodity, of greed. The upshot of extraordinary wealth was that Hewitt the compulsive collector could have anything he desired. Yet, as he voraciously pursued the next acquisition his relationship with the birds whose mortal remains he already possessed appears to have quickly become hollow. Their banishment to piles of anonymous boxes leads to the likely conclusion that whilst fabulously materially and financially endowed, in terms of mana Hewitt felt nothing – or if he did he was unwilling to share it, thereby rendering it impotent.

At the opposite pole, supercharged with the intangible qualities absent from Hewitt’s world yet of no material value, are stories – related not just orally but through image, object, song and action. Because of their critical function in maintaining the universal cycles these were – and still are – deemed sufficiently precious to have been passed on through successive generations across millennia; constantly mutating so as to maintain their power within shifting circumstances. In this way, the mythological huia and the great auk, vital components within cultures that sprung from the same landscapes as the birds themselves, are held in memory and are therefore, in a non-biological sense, extant.

But for how long? And of what does the rapid erosion of these vital capacitors of continuity and renewal speak? Very clearly their decline – or systemic suppression – in the colonial period mirrored exponential increases in dysfunction and disease within the cultures whose values they expressed.

For us in ours, communal gatherings in which stories were told – events that expressed and affirmed both social bonds and our place in the universe – have largely been supplanted and commodified within the insularly experienced realm of platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime. Journeys into nature, whether real or imagined, are increasingly supplanted by passive, sofa-bound consumption – at a cost to our physical, emotional and mental wellbeing.

We in Wales should therefore be concerned with how these poles are manifest in what is rather drily termed ‘the creative sector’. Here in a crystal clear reflection of our contemporary value system, primacy – presenting as a disproportionately excessive level of reward – is afforded to those who with no little profligacy nurture the culture of the sedentary ‘binge watcher’; a trade in products of mass consumption which whilst admittedly occasionally startlingly powerful, are all too often anodyne and rapidly banished to the back rooms of the digital void, just like the specimens in Hewitt’s boxes.

By contrast, those whose deeply felt calling lies in the maintenance of technologies emergent from and attuned to our neural hard-wiring – beautifully evolved survival mechanisms stemming from our experience of the landscape, the purpose of which are to uphold or amplify values of which the mythological huia, great auk and curlew speak – face very real hardship to the extent that it increasingly ceases to be impossible to function.

What does this say of our society and its values?

Whilst those of a reductive disposition will dismiss the value of the ‘spiritual’, the visceral impact of music alone – the earliest physical manifestations of which are flutes made from the wing bones of birds – shows very clearly that there is more to our humanity than functional rationality. And that the unquantifiable forces which lie beyond rather crudely defined ‘pragmatism’ very clearly exert power over the ‘objective’. Such power has a higher purpose than to merely boost the bottom line.

This is not to dismiss the value of profitability – rather to warn against placing it on society’s high altar at the expense of all else. As the very ancient Warddeken story ‘The Greedy Emu’ attests, greed invariably leads to a fall. And greed – by definition – is very simply taking more than is needed.

Thus, bound up in the mortal remains of three dead birds from the collection of Amgueddfa Cymru, we find a mirror held not just to our relationship with nature – but also to the way in which we communicate what we ourselves are. Our willingness to absorb and reflect on the lessons they present will dictate the future viability, both of species such as the curlew and our own.

We cannot continue as we are – our way is not working and the well-being of both our society and its environment are very clearly in sharp decline.

Can we then re-discover the means to find value and joy in that which cannot be counted, measured or owned?

We must hope so – our future depends on it.